Saturday, 6th of August 2011, was the day on which the “The Circular Room” took place for the first time.

Prior to the meeting, we let people suggest and vote for different topics in our Facebook forum. The majority voted for the topic “Who is Iranian? What makes you Iranian? Where is our home?”

“… If you want to know who is an Iranian, you should look for the answer to the question: ‘Who is not an Iranian!’…” (Ramin Jahanbagloo)

Already one hour before the start of the first “Circular Room” meeting, the organizers and the guests from the Berlin Simurgh group, which had developed this form of discussion, had arrived at the venue. Our guests wanted to support us during the “hour of birth” of our series of meetings. I have to admit that I was nervous. Will enough people show up? Will the technical equipment work properly? Will the discussion be lively and inspiring?

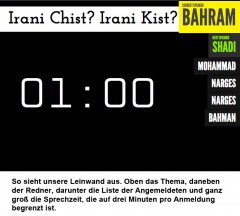

Following the discussion forum’s name, we put aside all tables and arranged the chairs in a circle. The topic, the allocated speaking time of the respective speaker as well as the list of speakers was shown on a big screen. The “Code of Conduct of the Circular Room” was distributed. We were ready to begin.

Typically Persian: The meeting was supposed to begin at 5 pm, but only 6 persons were present at that time. I started to question our communication channels. But in the course of the next 15 minutes, more and more people came in.

The mix of people was very interesting indeed: Young and old, people who have lived in Germany for a long time or who had just arrived here. It was definitely a colorful gathering. Before the meeting, people had had the opportunity to vote on the different discussion topics on our “Otaghe Gerd” site on Facebook. Most participants were interested in discussing the topic “Who is an Iranian? What does ‘Iranian’ mean?” during the first meeting.

As I could not find anybody in the run-up to the meeting who would voluntarily hold the introductory speech, I prepared some facts and figures from encyclopedias, history books and presentations, and summarized my findings to a 10 minute opening speech. One of my sources was Ramin Jahanbegloo. During a lecture on the same topic at the UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) in 2008, he said the following:

As I could not find anybody in the run-up to the meeting who would voluntarily hold the introductory speech, I prepared some facts and figures from encyclopedias, history books and presentations, and summarized my findings to a 10 minute opening speech. One of my sources was Ramin Jahanbegloo. During a lecture on the same topic at the UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) in 2008, he said the following:

“… If you want to know who is an Iranian, you should look for the answer to the question: ‘Who is not an Iranian!’...”

Furthermore, he talked about the “self-centrism” of old and strong nations like Iran, and of the “cosmo-centrism” of great nations which considered themselves the center of the world.

“… They were powerful and progressive compared to their neighbors. Hence, they were lacking the curiosity to look around and compare their own level of development with that of other nations. They were the measure of all things. They determined standards and the bounds of acceptability. Discussions, therefore, only took place within the society. Exchange with other societies was rare. However, when these strong societies enter into modern times, but standards and their horizon of social discourse cannot pass comparison with modernity anymore, and they, on the other side, have never learned to absorb new impulses through the exchange with the outside world, they will fall into crisis. On the one hand, they are cut off from themselves and not able to develop further through their own efforts. On the other, they are not able to learn from others. …”

In this age of globalization, don’t we, as post-modern human beings, have to detach ourselves from an out-dated concept of a “national identity”? That was one of the questions we discussed.

In case of Iran, the situation is further aggravated as Iranians tend to have a dualistic conception of the world: Either divine or diabolical, holy or evil. Such an identity always considers itself as pure and the other as impure.

When an identity deems itself as pure, unique and absolute, violence is always not far. You may ask yourself why? The reason is that this kind of identity rejects others. Hence, considering “being Iranian” a dualistic ideology, we will harm ourselves as well as the others. In the long term, it will end in self-destruction. However, if we see “being Iranian” linked to “not being Iranian”, the concept gets more flexible and tolerant. Depending on regional, historical or social developments, it can be viewed from different perspectives resulting into new and different answers. This approach always strives for interaction and exchange with other cultures and defines itself by looking at other cultures…”

The above passages are from Jahanbegloo`s lecture which I cited on that day. Afterwards the floor was open for discussion.

At first, the debate started very slowly and with some caution. Only a few persons expressed their wish to speak, but gradually more and more people put their names on the list. After some time, it was not possible to show all names on the screen and the stopwatch was glowing. Even during a break of only 10 minutes, people continued to discuss.

Where is the place of ethnic and religious minorities when defining a cultural identity? What about us, here in the Diaspora? How can we define our being and our affiliation? And do we really need to do so at all? In this age of globalization, don’t we, as post-modern human beings, rather have to detach ourselves from the out-dated concept of a “national identity”? How should one differentiate between a cultural and national identity? How important is the process of finding your own identity and defining yourself for the dialogue with others? How about the generation of Iranians which was born here in Germany and which has little contact to Iran, but still carries parts of the Iranian culture inside? Do they also feel like Iranians?

Those were only some of the questions which we discussed vigorously, but in a very polite and warm-hearted atmosphere, during that afternoon. Of course, we did not find the final answer to all those questions, but maybe that was exactly the right approach. Maybe it was simply about finding out how many different perceptions of concepts like “cultural identity”, “belongingness”, and “home” exist and how important or unimportant those concepts are for us. We noticed that some of us who only recently left Iran feel more cosmopolitan than some of those Iranians who have lived abroad for decades.

Maybe experiencing that we are united by many common views, but that there are differences and diverse concepts at the same time, was the best that could have happened to us.

Afterwards we went out to eat Chelo Kabab – without having made any arrangements before hand. It was just clear, in this point we were all soul mates.

The next day some participants posted links on our Facebook site that refer to texts on our first “Otaghe Gerd” topic. For all who would like to dig deeper on the subject: